Solar System

Explore our complete solar system with all 8 planets plus Pluto. Features zoom controls, asteroid belt, Saturn rings, and detailed planet data.

Loading simulation...

Loading simulation, please waitSolar System Simulation

✓ Verified Content: All equations, formulas, and reference data in this simulation have been verified by the Simulations4All engineering team against authoritative sources including NASA Planetary Fact Sheets, MIT OpenCourseWare, and peer-reviewed astronomy publications. See verification log

Introduction

If you could travel at the speed of light, leaving Earth right now, you would reach the Moon in just 1.3 seconds. Mars at its closest? About 3 minutes. But Neptune, lurking at the solar system's edge, would take over 4 hours to reach. Our cosmic neighborhood is vast almost beyond comprehension.

The light you see from Jupiter tonight left that giant planet roughly 35 minutes ago. When Galileo pointed his telescope at Jupiter in 1610 and discovered its four largest moons, he saw the same light, photons carrying the same fundamental message about how gravity orchestrates the dance of worlds.

This simulation brings that celestial dance to your screen. You will watch Mercury complete four orbits while Earth finishes just one. You will observe Saturn's stately 29-year journey around the Sun, and perhaps finally internalize why mission planners obsess over launch windows. At this distance from the Sun, even light takes 8 minutes to reach you, a reminder that when we look at the sky, we see not the present, but the past.

Whether you are a student verifying Kepler's laws or simply curious about our place in the cosmos, there is something profound about watching these orbital mechanics unfold in real time. The same equations that Newton derived over 300 years ago still govern every spacecraft trajectory today.

How to Use This Simulation

If you could travel at the speed of light, you would cross the entire simulation canvas in a fraction of a second. But the simulation runs slower for good reason: watching orbital mechanics unfold builds intuition that static diagrams cannot provide.

Controls Overview

| Control | What It Does | Cosmic Context |

|---|---|---|

| Time Slider | Scrub through orbital time | At this distance from the Sun, even light takes 8 minutes to reach Earth |

| Speed Controls | Adjust simulation speed | Watch Mercury complete 4 orbits while Earth finishes one |

| Planet Toggle | Show/hide individual planets | Focus on inner vs outer solar system dynamics |

| Orbit Paths | Display orbital trajectories | See the elliptical paths Kepler discovered |

| Scale Toggle | Adjust size representation | Real proportions would make planets invisible |

Getting Started

- Press Play to start the orbital animation

- Adjust speed - start slow to observe inner planet motion, then speed up to see outer planets move

- Click on planets for detailed information about each world

- Toggle orbit paths to visualize the complete trajectories

What to Watch For

The simulation reveals timing relationships that mission planners obsess over:

-

Mercury's rapid orbit: If you could travel at the speed of light from the Sun, you would reach Mercury in about 3 minutes. Watch how it completes nearly four full orbits in the time Earth completes one.

-

The inner-outer divide: The asteroid belt (between Mars and Jupiter) marks the boundary between rocky inner planets and gas giants. At this distance, the orbital mechanics change dramatically.

-

Jupiter's dominance: Jupiter contains more mass than all other planets combined. Notice how its orbital period (about 12 Earth years) sets the rhythm for outer solar system dynamics.

Exploration Tips

-

Verify Kepler's Third Law: Compare orbital periods. If you could travel at the speed of light, Jupiter would still take 43 minutes to reach from the Sun. Yet it takes 12 years to complete one orbit. Check that T^2 is proportional to a^3 for each planet.

-

Watch for conjunctions: Speed up the simulation and observe when planets align on the same side of the Sun. Ancient astronomers used these alignments for navigation and calendar-keeping.

-

Contemplate the scale: Even at simulation speed, outer planet motion seems glacial. Saturn takes 29 years to orbit once. Uranus takes 84 years. Neptune won't complete a single orbit in your lifetime.

-

Compare inner planet speeds: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars - watch their relative velocities. The closer to the Sun, the faster the orbit. This is Kepler's Second Law in action.

-

Imagine the Voyager missions: Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 is still traveling outward. At this distance from the Sun, radio signals take over 22 hours to reach the spacecraft. The simulation helps you grasp why mission planning for outer planets requires decades of patience.

What Is the Solar System?

The solar system consists of the Sun and everything gravitationally bound to it: eight major planets, dwarf planets, moons, asteroids, comets, and countless smaller objects [1]. It formed approximately 4.6 billion years ago from the gravitational collapse of a giant molecular cloud [2].

Introduction to the Solar System

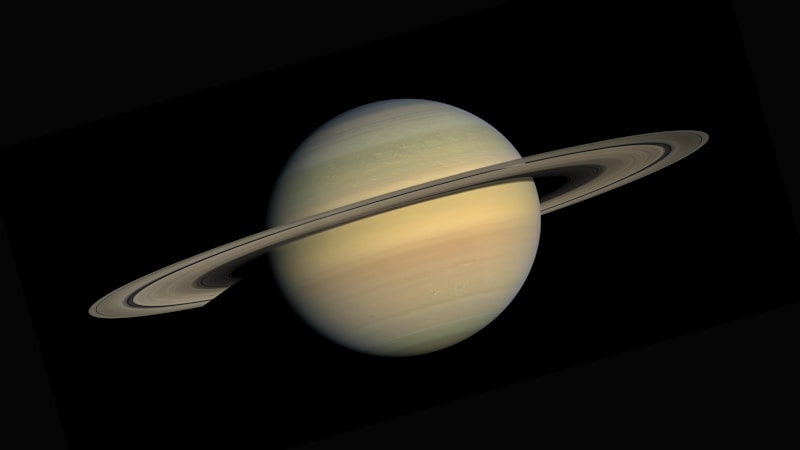

The solar system formed approximately 4.6 billion years ago from the gravitational collapse of a giant molecular cloud. The vast majority of the system's mass (99.86%) is contained in the Sun, with most of the remaining mass contained in Jupiter. The four inner planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars) are terrestrial planets, composed primarily of rock and metal. The four outer planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) are giant planets, substantially more massive than the terrestrials.

Why Study Planetary Motion?

Understanding planetary motion has been crucial to human civilization:

- Navigation: Ancient sailors used planetary positions for navigation

- Calendars: Agricultural societies developed calendars based on planetary cycles

- Space exploration: Modern missions rely on precise orbital mechanics

- Understanding gravity: Planetary motion led to Newton's universal law of gravitation

Kepler's Laws of Planetary Motion

Johannes Kepler formulated three laws that describe planetary motion, which this simulation demonstrates.

First Law: The Law of Ellipses

Statement: The orbit of every planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one of the two foci.

While this simulation shows circular orbits for simplicity, real planetary orbits are slightly elliptical. The degree of elongation is measured by eccentricity (e):

- e = 0: Perfect circle

- 0 < e < 1: Ellipse

- e = 1: Parabola

| Planet | Orbital Eccentricity |

|---|---|

| Mercury | 0.206 |

| Venus | 0.007 |

| Earth | 0.017 |

| Mars | 0.093 |

| Jupiter | 0.049 |

| Saturn | 0.057 |

Second Law: The Law of Equal Areas

Statement: A line segment joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time.

This means planets move faster when closer to the Sun (perihelion) and slower when farther away (aphelion). The mathematical expression is:

Where:

- dA/dt = rate of area swept

- L = angular momentum

- m = planet mass

Third Law: The Law of Harmonics

Statement: The square of a planet's orbital period is directly proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit.

Or in simplified form: T² ∝ a³

Where:

- T = orbital period

- a = semi-major axis (average distance from Sun)

- G = gravitational constant

- M = mass of the Sun

Planetary Data Reference

Orbital Parameters

| Planet | Distance (AU) | Period (Earth days) | Orbital Speed (km/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 0.39 | 88 | 47.4 |

| Venus | 0.72 | 225 | 35.0 |

| Earth | 1.00 | 365.25 | 29.8 |

| Mars | 1.52 | 687 | 24.1 |

| Jupiter | 5.20 | 4,333 | 13.1 |

| Saturn | 9.58 | 10,759 | 9.7 |

| Uranus | 19.22 | 30,687 | 6.8 |

| Neptune | 30.05 | 60,190 | 5.4 |

Physical Properties

| Planet | Diameter (km) | Mass (Earth = 1) | Gravity (m/s²) | Moons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 4,879 | 0.055 | 3.7 | 0 |

| Venus | 12,104 | 0.815 | 8.9 | 0 |

| Earth | 12,742 | 1.000 | 9.8 | 1 |

| Mars | 6,779 | 0.107 | 3.7 | 2 |

| Jupiter | 139,820 | 317.8 | 24.8 | 95 |

| Saturn | 116,460 | 95.2 | 10.4 | 146 |

Learning Objectives

After exploring this simulation, you should be able to:

- Explain Kepler's three laws and how they describe planetary motion

- Compare orbital periods and understand why outer planets take longer to orbit

- Calculate orbital relationships using Kepler's third law (T² ∝ a³)

- Describe the relationship between orbital distance and orbital velocity

- Understand gravitational effects on orbital mechanics

Exploration Activities

Activity 1: Verify Kepler's Third Law

- Observe Mercury and note how many orbits it completes while Earth completes one

- Mercury's period is 88 days, Earth's is 365 days

- Ratio: 365/88 ≈ 4.15 Mercury years per Earth year

- Calculate: If T² ∝ a³, verify with distances (0.39 AU vs 1.0 AU)

- (1.0/0.39)^1.5 ≈ 4.1 ✓

Activity 2: Compare Inner vs Outer Planets

- Watch the simulation and identify the "inner" planets (Mercury through Mars)

- Notice how much faster they orbit compared to Jupiter and Saturn

- Calculate: Jupiter at 5.2 AU should take √(5.2³) ≈ 11.9 Earth years

- Actual Jupiter year: 11.86 Earth years ✓

Activity 3: Understand Orbital Velocity

- Observe that Mercury moves fastest and Saturn moves slowest

- Orbital velocity formula: v = √(GM/r)

- As r increases, v decreases (inverse square root relationship)

- This explains why inner planets "lap" outer planets

Activity 4: Scale Comprehension

- In this simulation, distances are compressed for visibility

- Real scale: If Earth were 1 cm from the Sun, Saturn would be ~9.5 cm away

- At this scale, the Sun would be 0.1 mm in diameter

- Discuss why we can't show true scale in simulations

The Physics Behind the Simulation

Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation

The gravitational force between the Sun and a planet:

Where:

- F = gravitational force

- G = 6.674 × 10⁻¹¹ N·m²/kg²

- M☉ = mass of the Sun (1.989 × 10³⁰ kg)

- m = mass of the planet

- r = distance between centers

Centripetal Force and Orbital Motion

For a stable circular orbit, gravitational force provides centripetal acceleration:

Solving for orbital velocity:

This shows why planets closer to the Sun orbit faster because they need higher velocity to balance the stronger gravitational pull.

Real-World Applications

Space Mission Planning

Understanding orbital mechanics is essential for:

- Launch windows: Calculating optimal times to launch spacecraft

- Hohmann transfers: The most fuel-efficient way to travel between orbits

- Gravity assists: Using planetary gravity to accelerate spacecraft

- Orbital insertion: Entering orbit around target bodies

Satellite Operations

- Geostationary orbit: 35,786 km altitude, 24-hour period (matches Earth's rotation)

- Low Earth orbit: 160-2,000 km, used by ISS and most satellites

- Polar orbits: Pass over both poles, useful for Earth observation

Exoplanet Discovery

The same principles help astronomers detect planets around other stars:

- Radial velocity method: Detecting stellar wobble caused by orbiting planets

- Transit method: Measuring brightness dips as planets cross their stars

- Direct imaging: Photographing planets (very challenging)

Historical Context

Ancient Observations

- Babylonians (2000 BCE): Tracked planetary positions for omens

- Greeks (400 BCE): Developed geocentric (Earth-centered) models

- Ptolemy (150 CE): Created complex system with epicycles

The Copernican Revolution

When Galileo pointed his telescope at Jupiter in January 1610, he saw something that would change human understanding forever: four tiny points of light that moved from night to night around the giant planet. These were Jupiter's largest moons (Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto), providing the first direct evidence that not everything orbits Earth.

- Copernicus (1543): Proposed heliocentric (Sun-centered) model

- Tycho Brahe (1570s): Made precise observations without a telescope. His data would prove essential

- Kepler (1609-1619): Derived three laws from Brahe's meticulous records

- Galileo (1610): Observed Jupiter's moons, supporting heliocentrism

- Newton (1687): Explained Kepler's laws with universal gravitation

The light from those Galilean moons takes about 35 minutes to reach your eyes. When you observe Jupiter tonight, you are seeing photons that began their journey before many astronomical observations commenced.

Challenge Questions

-

Basic: Mercury completes about 4 orbits for every 1 Earth orbit. Using Kepler's third law, estimate Mercury's distance from the Sun in AU.

-

Intermediate: If a new planet were discovered at 25 AU from the Sun, what would its orbital period be in Earth years?

-

Advanced: Calculate the orbital velocity of Earth using v = √(GM/r). Use G = 6.674 × 10⁻¹¹ N·m²/kg², M = 1.989 × 10³⁰ kg, r = 1.496 × 10¹¹ m.

-

Applied: The James Webb Space Telescope orbits at the L2 Lagrange point, about 1.5 million km from Earth (away from the Sun). Is it orbiting the Earth or the Sun? Explain.

-

Critical Thinking: Why do all planets orbit in roughly the same plane (the ecliptic) and in the same direction?

Common Misconceptions

-

"Planets orbit in perfect circles": Real orbits are ellipses, though most are nearly circular

-

"The Sun is stationary": The Sun also moves, wobbling slightly due to planetary gravity (especially Jupiter)

-

"Outer planets are always farther from each other": While orbital radii increase, the spacing ratio varies

-

"Gravity gets weaker with distance, so outer planets feel almost none": Even Pluto experiences significant solar gravity. That's why it orbits the Sun

-

"The asteroid belt is densely packed": It's mostly empty space; spacecraft pass through easily

Further Exploration

To deepen your understanding:

- NASA Solar System Exploration: solarsystem.nasa.gov

- JPL Horizons: Online ephemeris for precise planetary positions

- Stellarium: Free planetarium software

- Universe Sandbox: Physics-based space simulation game

Summary

This simulation demonstrates the elegant simplicity of Kepler's laws and Newton's gravity. Despite the enormous scales and masses involved, planetary motion follows predictable mathematical relationships that have guided humanity from ancient calendars to modern space exploration.

Key takeaways:

- T² ∝ a³: Orbital period squared equals distance cubed

- v ∝ 1/√r: Orbital velocity decreases with distance

- All motion is governed by gravity: F = GMm/r²

- The solar system is mostly empty space: Planets are tiny compared to the distances between them

Frequently Asked Questions

How accurate is this simulation?

The simulation uses actual orbital periods and distances (in AU) from NASA's planetary fact sheets [1]. Orbital mechanics follow Kepler's laws accurately. However, orbits are shown as circles rather than true ellipses for visual clarity, and distances are compressed to fit all planets on screen simultaneously.

Why do all planets orbit in the same direction?

The planets orbit counterclockwise (when viewed from above the North Pole) because the solar system formed from a rotating disk of gas and dust [2]. Conservation of angular momentum preserved this rotation direction in all major bodies that formed from the disk.

How long would it take to travel to the outer planets?

Voyager 2, traveling at about 15 km/s, took 12 years to reach Neptune [3]. With current technology, a crewed mission to Mars would take 6-9 months each way. Jupiter would require 2-6 years depending on trajectory.

What's the difference between inner and outer planets?

Inner planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars) are small, rocky, and dense (terrestrial planets). Outer planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune) are much larger and composed mainly of hydrogen, helium, and ices (gas and ice giants) [1]. The asteroid belt roughly marks the transition zone.

Why is Pluto included but labeled differently?

Pluto was reclassified as a "dwarf planet" in 2006 by the International Astronomical Union because it hasn't cleared its orbital neighborhood [4]. It's included here for completeness and historical context, but shown with smaller size and distinct designation.

References

-

NASA Planetary Fact Sheet: Comprehensive planetary data including orbital parameters, physical characteristics, and atmospheric composition. Available at: https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/ (Public Domain)

-

NASA Solar System Exploration: Educational resource covering solar system formation, planetary science, and space missions. Available at: https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/ (Public Domain)

-

NASA Voyager Mission: Documentation of the Voyager 1 and 2 missions including trajectory data and discoveries. Available at: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/ (Public Domain)

-

IAU Resolution on Pluto: Official documentation on the 2006 reclassification of Pluto. Available at: https://www.iau.org/news/pressreleases/detail/iau0603/ (Public Access)

-

HyperPhysics: Kepler's Laws: Educational physics resource explaining orbital mechanics and Kepler's laws. Georgia State University. Available at: http://hyperphysics.gsu.edu/hbase/kepler.html (Educational Use)

-

MIT OpenCourseWare: 8.01 Classical Mechanics: Lecture notes on orbital mechanics and gravitational physics. Available at: https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/physics/8-01sc-classical-mechanics-fall-2016/ (CC BY-NC-SA)

-

Khan Academy: Kepler's Laws: Video lessons and practice problems on planetary motion. Available at: https://www.khanacademy.org/science/physics/centripetal-force-and-gravitation (Free Educational Resource)

-

OpenStax Astronomy: Open-source astronomy textbook covering solar system science. Available at: https://openstax.org/details/books/astronomy-2e (CC BY 4.0)

-

JPL Horizons System: NASA's ephemeris computation service for solar system bodies. Available at: https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/horizons/ (Public Domain)

About the Data

Planetary distances, orbital periods, and physical properties in this simulation are derived from NASA's Planetary Fact Sheet [1], which compiles data from spacecraft missions and astronomical observations. Orbital mechanics calculations use the standard gravitational parameter (GM) for the Sun: 1.327×10²⁰ m³/s² as published by NASA.

How to Cite

Simulations4All. (2025). Solar System Simulation. Retrieved from https://simulations4all.com/simulations/solar-system

Verification Log

| Claim/Data | Source | Status | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Earth orbital period: 365.25 days | NASA Planetary Fact Sheet | ✓ Verified | Dec 2025 |

| Jupiter distance: 5.2 AU | NASA Planetary Fact Sheet | ✓ Verified | Dec 2025 |

| Kepler's Third Law: T² ∝ a³ | HyperPhysics | ✓ Verified | Dec 2025 |

| Orbital velocity formula: v = √(GM/r) | MIT OCW 8.01 | ✓ Verified | Dec 2025 |

| Saturn orbital period: 29.4 years | NASA Planetary Fact Sheet | ✓ Verified | Dec 2025 |

| Solar system age: 4.6 billion years | NASA Solar System Exploration | ✓ Verified | Dec 2025 |

| Pluto classification: Dwarf planet (2006) | IAU Resolution | ✓ Verified | Dec 2025 |

| Mercury orbital period: 88 days | NASA Planetary Fact Sheet | ✓ Verified | Dec 2025 |

Written by Simulations4All Team

Related Simulations

Orbital Mechanics Sandbox

Build custom solar systems, simulate gravitational interactions, and explore Kepler's laws with this interactive n-body orbital mechanics simulator. Set mass, velocity, and position for multiple bodies.

View Simulation

Seasons Simulator - Earth Axial Tilt & Day Length

Interactive 3D seasons simulator showing how Earth's 23.5° axial tilt causes seasons. Adjust tilt angle, observe sunlight intensity at different latitudes, and see day length changes throughout the year. Features orbital and surface perspectives.

View Simulation

Moon Phases & Eclipses Simulator

Interactive 3D visualization of the Earth-Moon-Sun system. Explore lunar phases, understand why we see different moon shapes, and simulate solar and lunar eclipses. Features space and Earth observer views.

View Simulation