Orbital Mechanics Sandbox

Build custom solar systems, simulate gravitational interactions, and explore Kepler's laws with this interactive n-body orbital mechanics simulator. Set mass, velocity, and position for multiple bodies.

Loading simulation...

Loading simulation, please waitOrbital Mechanics Sandbox: Build Your Own Solar System

✓ Verified Content: All equations, formulas, and reference data in this simulation have been verified by the Simulations4All engineering team against authoritative sources including NASA JPL, NIST CODATA, and classical mechanics textbooks. See verification log

Introduction

The Voyager 1 spacecraft, launched in 1977, is now over 24 billion kilometers from Earth. At this distance, light takes more than 22 hours to travel between the probe and Mission Control. Every course correction that guided Voyager past Jupiter and Saturn relied on the same orbital mechanics equations you will explore in this simulation, equations first derived by Johannes Kepler 400 years ago.

When Newton watched an apple fall (whether or not that story is apocryphal), he realized that the same force pulling fruit to the ground also held the Moon in its orbit. If you could throw a ball fast enough (about 8 kilometers per second), it would fall continuously around Earth rather than hitting the surface. That is what orbiting means: perpetual falling, perpetual missing.

This simulation provides a hands-on laboratory for exploring that gravitational dance. Unlike static textbook diagrams, you can watch orbits evolve in real time, add or remove celestial bodies, and immediately observe how changes in mass, position, or velocity affect the entire system. The light from our Sun takes 8 minutes to reach Earth, 43 minutes to reach Jupiter, and over 4 hours to reach Neptune. In this sandbox, you can compress those timescales and watch years of orbital motion unfold in seconds.

Whether you are a physics student verifying Kepler's third law, an astronomy enthusiast recreating planetary configurations, or simply curious about how gravity sculpts the cosmos, this simulation offers the flexibility and quantitative feedback that brings celestial mechanics to life.

How to Use This Simulation

Quick Start Guide

- Select a Preset: Click "Sun + Earth" under Preset Scenarios to load a working solar system

- Press Play: Click the green "Play" button to start the simulation

- Select a Body: Click on any planet or star to see its orbital data

- Adjust Speed: Use the Speed slider to run faster (5x) or slower (0.1x)

Control Panel Reference

| Control | Function |

|---|---|

| ▶ Play / ⏸ Pause | Start or pause the simulation |

| ↺ Reset | Return all bodies to initial positions and clear trails |

| + / − | Zoom in/out (or use scroll wheel) |

| ⬜ Fit | Auto-zoom to show all bodies |

| Speed Slider | Adjust simulation speed from 0.1x to 10x |

| ☑ Trails | Show/hide orbital path trails |

| ☑ Vectors | Show/hide velocity vectors on each body |

| ☑ Perihelion | Show/hide P (perihelion) and A (aphelion) markers |

Interactive Canvas Controls

- Scroll wheel: Zoom in/out centered on cursor

- Click + Drag: Pan the view

- Single click on body: Select it to view orbital data

- Double-click on empty space: Add a new body at that location

Adding Custom Bodies

Use the "Add New Body" panel on the right:

- Type: Choose Planet, Star, or exotic types (Black Hole, Neutron Star, etc.)

- Name: Give your body a memorable name

- Mass: Set mass in x10^24 kg (Earth = 5.97, Sun = 1,989,000)

- Position: X and Y coordinates in AU (1 AU = Earth-Sun distance)

- Velocity: X and Y velocity in km/s (Earth orbital = 29.78 km/s)

- Color: Pick a color for visualization

- Click "+ Add Body" to create it

Pro Tip: For a circular orbit, set velocity perpendicular to the radius with magnitude v = √(GM/r). For Earth's distance (1 AU) from the Sun, that's ~29.78 km/s.

Understanding the Data Panels

Orbital Data (when body selected):

- Distance: Current distance from central body (or CoM for stars)

- Perihelion/Aphelion: Closest and farthest points recorded during orbit

- Eccentricity: Orbit shape (0 = circle, 0.9+ = highly elliptical)

- Orbit Type: "Bound" (orbiting) or "Escape" (leaving system)

Velocity Breakdown:

- Tangential: Velocity perpendicular to radius (keeps you in orbit)

- Radial: Velocity toward/away from central body

- For circular orbits: 100% tangential, 0% radial

Motion Graph:

- Tracks velocity, distance, or kinetic energy over time

- Use dropdown to select which body to track

- Great for visualizing orbital oscillations in elliptical orbits

Preset Scenarios

Classic Tab:

- Sun + Earth: Simple two-body system demonstrating circular orbit

- Earth + Moon: Three-body system with lunar orbit

- Binary Stars: Two equal-mass stars orbiting common center

- Inner Planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars with accurate parameters

- Figure-8: Famous stable three-body choreography

- Empty: Clear canvas for custom systems

Exotic Tab:

- Black Hole + Star: Stellar black hole with companion

- BH + Planets: Supermassive black hole (Interstellar-inspired)

- NS Binary: Two neutron stars (gravitational wave source)

- White Dwarf: Compact stellar remnant with planet

- Red Giant: Expanded star engulfing inner planets

- Triple System: Hierarchical three-star configuration

Challenges Panel

Test your understanding with built-in challenges:

- Circular Orbit: Create a perfectly circular orbit

- Escape Velocity: Launch a body to escape the system

- Binary System: Create two bodies orbiting their common center

- Figure-8: Achieve the stable three-body figure-8 configuration

Tips for Best Experience

- Start simple: Begin with Sun + Earth before complex systems

- Watch the trails: Orbital paths reveal whether orbits are stable

- Check eccentricity: Near 0 means circular; high values mean elongated

- Use the graph: Periodic patterns indicate stable orbits

- Try the challenges: They teach orbital mechanics concepts hands-on

- Zoom for detail: Miller's orbit near a black hole shows extreme effects when zoomed in

Simulation Physics and Accuracy

This simulation implements physically accurate gravitational dynamics using established computational methods:

Velocity Verlet Integration: Rather than simple Euler integration (which accumulates energy errors over time), this simulation uses the Velocity Verlet algorithm, a symplectic integrator that conserves total mechanical energy over long time periods. This is the same class of integrator used in professional astronomy software and molecular dynamics simulations [1].

Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation: Every body attracts every other body with force F = Gm₁m₂/r². The gravitational constant G = 6.674×10⁻¹¹ N·m²/kg² matches the CODATA 2018 recommended value.

N-Body Calculations: Unlike simplified two-body simulators, this sandbox computes gravitational interactions between ALL bodies simultaneously. Add three stars and watch chaotic three-body dynamics emerge, the same phenomena that make real stellar systems unpredictable.

Verified Preset Values: All preset scenarios use real astronomical data from NASA JPL:

- Sun mass: 1.989×10³⁰ kg ✓

- Earth mass: 5.972×10²⁴ kg ✓

- Earth orbital velocity: 29.78 km/s ✓

- 1 AU = 1.496×10¹¹ m ✓

The circular orbital velocity formula v = sqrt(GM/r) predicts 29.783 km/s at 1 AU. Our preset value of 29.78 km/s produces near-circular orbits as expected.

Understanding Velocity Components: Tangential vs Radial

One of the most important concepts for understanding orbital mechanics is the decomposition of velocity into its tangential and radial components [2].

Tangential Velocity (v_tan) is the component perpendicular to the line connecting the orbiting body to the central mass. This component:

- Creates and maintains angular momentum

- Determines whether you stay in orbit or fall inward

- At perihelion: v_tan is at maximum (angular momentum conservation: L = mvr)

- For a circular orbit: ALL velocity is tangential (v_rad = 0)

Radial Velocity (v_rad) is the component along the line connecting the bodies. This component:

- Positive value = moving away from the central body

- Negative value = moving toward the central body

- Determines how your distance changes over time

- At perihelion and aphelion: v_rad = 0 (momentarily neither approaching nor receding)

Why This Matters: The ratio of tangential to radial velocity determines orbit shape. In your scenario where the planet "fell toward the Sun," the initial velocity was mostly radial (outward), not tangential. With little tangential velocity, there was minimal angular momentum, causing a highly elliptical plunging orbit rather than a circular one.

Key Insight: To create a circular orbit, set velocity PERPENDICULAR to the radius (pure tangential) at the correct magnitude: v = √(GM/r).

Perihelion and Aphelion: The Extremes of Orbit

In any elliptical orbit, two special points define the orbital boundaries [3]:

Perihelion (P): The point of closest approach to the central body.

- Marked with a red "P" in the simulation

- Velocity is MAXIMUM here (kinetic energy is highest)

- Radial velocity = 0 at this instant

- All velocity is tangential at perihelion

- For Earth: 147.1 million km (occurs around January 3)

Aphelion (A): The point farthest from the central body.

- Marked with a blue "A" in the simulation

- Velocity is MINIMUM here (kinetic energy is lowest)

- Radial velocity = 0 at this instant

- All velocity is tangential at aphelion

- For Earth: 152.1 million km (occurs around July 4)

The Physics Behind This: Angular momentum conservation (L = mvr) requires that as distance decreases, velocity must increase proportionally. At perihelion, r is minimum so v is maximum. At aphelion, r is maximum so v is minimum.

Calculating Orbital Parameters:

- Semi-major axis: a = (r_perihelion + r_aphelion) / 2

- Eccentricity: e = (r_aphelion - r_perihelion) / (r_aphelion + r_perihelion)

- For a circle: e = 0 (perihelion = aphelion)

Collision Detection and the Roche Limit

Real celestial bodies have physical size, and this simulation now models what happens when they get too close [8].

Physical Collision: When the distance between two bodies becomes less than the sum of their radii, they collide. In this simulation:

- Bodies merge on collision (conservation of momentum)

- The larger body absorbs the smaller

- Combined mass = m₁ + m₂

- New velocity preserves total momentum: v_new = (m₁v₁ + m₂v₂) / (m₁ + m₂)

The Roche Limit: Before physical collision, a fascinating phenomenon can occur: tidal destruction. The Roche limit is the distance within which tidal forces will tear apart a smaller body held together only by its own gravity [8].

Where:

- R_M = radius of the larger body

- ρ_M = density of the larger body

- ρ_m = density of the smaller body

Real Examples:

- Saturn's rings exist within Saturn's Roche limit, where a moon that ventured too close was torn apart

- Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 broke apart when it passed within Jupiter's Roche limit in 1992, before impacting in 1994

In the simulation, you'll see a warning when a body enters the Roche limit of a much larger one.

Exotic Celestial Bodies: Beyond Ordinary Stars

The light you see from the nearest black hole candidate, V616 Monocerotis, left that system about 3,000 years ago, around the time ancient Greeks were developing the first astronomical theories. At this distance, we can only observe the effects of the black hole's gravity on its companion star. The universe contains objects far stranger than familiar stars and planets, and this simulation models several of them with physically accurate parameters.

Black Holes: Where Gravity Wins

A black hole forms when a massive star exhausts its nuclear fuel and collapses under its own gravity. If the collapsing core exceeds roughly 3 solar masses, no known force can halt the collapse. The star crushes itself into a singularity of infinite density [9].

The Schwarzschild Radius: The defining feature of a non-rotating black hole is its event horizon, the boundary beyond which nothing, not even light, can escape. Karl Schwarzschild calculated this radius in 1916 [10]:

Where c = 299,792,458 m/s is the speed of light. For a 10 solar-mass black hole, r_s ≈ 30 km. This simulation accurately calculates the Schwarzschild radius for any black hole mass.

What Happens at the Event Horizon: In the simulation, any body crossing the event horizon is absorbed. Its mass adds to the black hole's mass, and the Schwarzschild radius grows accordingly. This models real accretion, though actual black holes also radiate energy through Hawking radiation (too slow to observe on human timescales) [11].

The Photon Sphere: At exactly 1.5 times the Schwarzschild radius, light can orbit the black hole in unstable circular paths. The simulation renders this as a distinct ring. Photons here are doomed: any perturbation sends them into the black hole or outward to escape.

Practical Insight: To orbit a 10 solar-mass black hole at 10 Schwarzschild radii (300 km), you'd need v = 94,000 km/s, about 31% the speed of light. Try creating such an orbit in the simulation!

Neutron Stars: Matter at Nuclear Density

When stars between roughly 8-25 solar masses exhaust their fuel, the core collapses so violently that protons and electrons merge into neutrons. The result is a neutron star, essentially a giant atomic nucleus 20 km across, containing 1.4-2 solar masses [12].

Extreme Properties:

- Density: ~10¹⁷ kg/m³ (a teaspoon weighs ~10 billion tons)

- Surface gravity: ~10¹¹ m/s² (about 200 billion times Earth's)

- Escape velocity: ~100,000 km/s (1/3 the speed of light)

- Spin rate: Up to 716 rotations per second (PSR J1748-2446ad)

In the Simulation: Neutron stars are rendered with a distinctive pulsing glow, representing the intense radiation from their magnetic poles. Their tiny physical radius (12 km default) means planets can orbit remarkably close without collision.

Binary Neutron Stars and Gravitational Waves: The simulation includes a "Neutron Binary" preset. When two neutron stars orbit each other closely, they emit gravitational waves and spiral inward over time. This was observed directly by LIGO in 2017 (GW170817), the first gravitational wave detection from neutron stars [13].

White Dwarfs: Stellar Remnants in Equilibrium

Most stars, including our Sun, end their lives as white dwarfs. When a star up to ~8 solar masses exhausts its hydrogen, it sheds its outer layers as a planetary nebula, leaving behind a dense core of carbon and oxygen [14].

Electron Degeneracy Pressure: White dwarfs are supported not by thermal pressure (like normal stars) but by electron degeneracy pressure, a quantum mechanical effect where electrons resist being compressed into the same quantum state. This creates a remarkable inverse relationship:

Mass-Radius Relation: More massive white dwarfs are SMALLER. The increased gravity compresses the degenerate matter further. A 1 solar-mass white dwarf has radius ~6,000 km (Earth-sized), while a 0.5 solar-mass white dwarf has radius ~8,500 km.

The Chandrasekhar Limit: Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar proved that no white dwarf can exceed ~1.44 solar masses [15]. Beyond this, electron degeneracy pressure fails and the star collapses further, into a neutron star or black hole. This limit is crucial for Type Ia supernovae, used as "standard candles" to measure cosmic distances.

In the Simulation: White dwarfs render with a pale blue-white glow. Their small size allows planets to orbit at distances of just a few stellar radii, creating extreme temperature variations between day and night sides.

Red Giants: The Bloated Phase

Before becoming white dwarfs, Sun-like stars swell into red giants. When core hydrogen exhausts, shell hydrogen burning around the inert helium core causes the outer layers to expand dramatically [16].

Scale of Expansion: A red giant can reach 100-200 times the Sun's current radius. When our Sun becomes a red giant in ~5 billion years, it will engulf Mercury and Venus, and possibly Earth.

In the Simulation: Red giants are rendered with layered orange-red coloring showing their diffuse outer atmosphere. The "Red Giant System" preset demonstrates planetary engulfment, where inner planets are swallowed as the star expands.

Planetary Survival: Planets at sufficient distance survive the red giant phase. In fact, planets can be pushed outward as the star loses mass, since orbital radius scales as r ∝ 1/M for constant angular momentum. Mars may survive our Sun's red giant phase.

Multi-Star Systems: Complex Gravitational Dance

Over half of all stars exist in binary or multiple systems. This simulation lets you explore the gravitational dynamics of multi-star configurations that would be impossible to observe evolving in real time [17].

Hierarchical Triples: Stable three-star systems typically have a "hierarchical" structure, a close binary with a distant third companion. The "Triple System" preset demonstrates this: two stars orbit each other closely while a third orbits the pair at greater distance.

Mass Transfer in Binaries: When stars in a binary system have different masses, the more massive one evolves faster. If it becomes a red giant while its companion is still a main-sequence star, mass can transfer through the inner Lagrange point. This can create exotic systems like cataclysmic variables and X-ray binaries.

Stability Considerations: Three-body systems are inherently chaotic. Small perturbations grow exponentially, and the simulation demonstrates this beautifully. Try perturbing a figure-8 three-body orbit by 1% and watch stability break down.

Reference Data: Exotic Body Properties

| Body Type | Typical Mass | Typical Radius | Density (kg/m³) | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black Hole | 5-100 M☉ | r_s = 2GM/c² | N/A (singularity) | Event horizon |

| Neutron Star | 1.4-2 M☉ | ~12 km | ~10¹⁷ | Nuclear density |

| White Dwarf | 0.5-1.4 M☉ | ~6,000 km | ~10⁹ | Electron degeneracy |

| Red Giant | 0.5-8 M☉ | 50-200 R☉ | ~10⁻⁴ | Diffuse envelope |

Data sourced from NASA stellar evolution models and Shapiro & Teukolsky (1983) [18].

Types of Orbits and Their Characteristics

Orbital mechanics describes several distinct orbit types, each determined by a body's velocity relative to its distance from the central mass [2].

Circular Orbits occur when an object's velocity exactly matches the circular orbital velocity v = √(GM/r). The object maintains constant distance from the central body, tracing a perfect circle. Earth's orbit around the Sun approximates this shape, with an eccentricity of only 0.017.

Elliptical Orbits result when velocity differs from circular orbital velocity but remains below escape velocity. The orbit becomes an elongated ellipse, with the central body at one focus. Comets and many asteroids follow highly elliptical paths, diving close to the Sun at perihelion before swinging far out at aphelion.

Parabolic Trajectories represent the boundary case where velocity exactly equals escape velocity. The object has precisely zero total energy and will reach infinite distance with zero velocity. While mathematically important, true parabolic orbits are unstable: any perturbation pushes them into elliptical or hyperbolic paths.

Hyperbolic Trajectories occur when velocity exceeds escape velocity. The object has positive total energy and will escape the gravitational field entirely, approaching a constant velocity at infinite distance. Voyager 1 and 2 follow hyperbolic trajectories relative to the Sun.

Key Parameters and Variables

| Parameter | Symbol | SI Unit | Typical Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gravitational Constant | G | N·m²/kg² | 6.674×10⁻¹¹ |

| Central Body Mass | M | kg | Sun: 1.989×10³⁰, Earth: 5.972×10²⁴ |

| Orbital Radius | r | m | Earth-Sun: 1.496×10¹¹ (1 AU) |

| Orbital Velocity | v | m/s | Earth: 29,780 |

| Orbital Period | T | s | Earth: 3.156×10⁷ (365.25 days) |

| Eccentricity | e | dimensionless | Circle: 0, Earth: 0.017, Pluto: 0.249 |

| Semi-major Axis | a | m | Determines orbital energy |

| Specific Orbital Energy | ε | J/kg | Negative for bound orbits |

Essential Orbital Mechanics Equations

The mathematics of orbital motion derives from Newton's law of universal gravitation and conservation principles [3].

Gravitational Force:

Every mass attracts every other mass with force proportional to their masses and inversely proportional to the square of their separation. This inverse-square relationship produces the elegant closed orbits Kepler observed.

Circular Orbital Velocity:

For circular motion, gravitational force must exactly balance centripetal acceleration. This equation shows why planets closer to the Sun move faster: Mercury orbits at 47.87 km/s while Neptune crawls at 5.43 km/s.

Escape Velocity:

Escape velocity exceeds circular velocity by exactly √2 ≈ 1.414. From Earth's surface, v_escape = 11.2 km/s. Spacecraft must reach or exceed this speed (relative to Earth) to leave our planet permanently.

Kepler's Third Law:

The orbital period squared is proportional to the semi-major axis cubed. This remarkable relationship allowed Kepler to deduce planetary distances knowing only their periods, a technique still used today for exoplanet detection.

Specific Orbital Energy:

Total mechanical energy per unit mass determines orbit type: ε < 0 means bound (elliptical), ε = 0 means parabolic, ε > 0 means hyperbolic. This quantity remains constant throughout an orbit.

Learning Objectives

After working with this simulation, you should be able to:

- Calculate circular orbital velocity for any mass-distance combination

- Predict whether a given initial velocity produces a bound or escape trajectory

- Explain why orbital period increases with distance from the central body

- Describe how eccentricity affects orbital shape and velocity variations

- Apply Kepler's third law to determine unknown orbital parameters

- Analyze n-body gravitational interactions and identify stable configurations

- Design transfer orbits between different orbital radii (Hohmann transfers)

Guided Exploration Activities

Activity 1: Verify Circular Orbital Velocity

Setup: Load the "Sun + Earth" preset. Earth starts at 1 AU with v = 29.78 km/s.

Steps:

- Select Earth and observe the "Orbit Type: Bound" indicator

- Click "Empty" preset, then add Sun (mass = 1989000 ×10²⁴ kg at origin)

- Add a test planet at x = 1 AU, y = 0, with vy = 30 km/s (slightly above circular)

- Run simulation and watch the orbit elongate into an ellipse

- Reset and try vy = 29.78 km/s exactly and observe near-circular orbit

Discussion: The circular orbit velocity formula v = √(GM/r) predicts v = 29.78 km/s at 1 AU from a solar-mass star. Even 1% deviation from this value produces measurable eccentricity.

Activity 2: Explore Kepler's Third Law

Setup: Load "Inner Planets" preset showing Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars.

Steps:

- Select Mercury (0.387 AU) and note its velocity (~47.9 km/s)

- Watch one complete orbit and count approximate days

- Select Earth (1 AU, 29.78 km/s) and time its orbit

- Calculate the ratio (T_Mercury/T_Earth)² and compare to (a_Mercury/a_Earth)³

Expected Result: Mercury's period is ~88 days, Earth's is 365 days. The ratio (88/365)² ≈ 0.058, and (0.387/1)³ ≈ 0.058. Kepler's third law holds!

Activity 3: Achieve Escape Velocity

Setup: Start with Sun + Earth preset.

Steps:

- Calculate escape velocity at Earth's position: v_esc = √2 × 29.78 ≈ 42.1 km/s

- Reset and modify Earth's initial vy to 42 km/s

- Run simulation and observe the trajectory curving away from circular

- Check the "Orbit Type" indicator (it should change to "Escape")

- Try vy = 41 km/s and observe the difference

Discussion: At exactly escape velocity, the orbit becomes parabolic. Slightly below, the object returns; slightly above, it escapes permanently.

Activity 4: Create a Stable Binary Star System

Setup: Load "Binary Stars" preset.

Steps:

- Observe how both stars orbit their common center of mass

- Note that with equal masses, both orbits have equal size

- Modify one star's mass to 0.5× the other

- Watch how the more massive star orbits closer to the center of mass

- Experiment with initial velocities to maintain stability

Physics Insight: In binary systems, both bodies orbit the barycenter (center of mass). The ratio of orbital radii equals the inverse mass ratio: r₁/r₂ = m₂/m₁.

Activity 5: Explore Black Hole Event Horizons

Setup: Load the "Black Hole + Star" preset from the Exotic tab.

Steps:

- Observe the black hole's rendering, noting the event horizon (black circle), photon sphere (thin ring at 1.5xr_s), and accretion glow

- Watch the companion star's orbit and notice the extreme orbital velocity needed to stay bound

- Use the data readout to find the Schwarzschild radius (displayed in km)

- Try adding a planet at 2x the star's orbital radius (will it survive?)

- Calculate: For a 10 M☉ black hole, verify r_s = 2GM/c² ≈ 30 km

Physics Insight: The event horizon isn't a physical surface. It's the point where escape velocity equals the speed of light. Nothing special happens to an infalling object at the horizon (from their perspective), but they can never return.

Activity 6: Watch Planetary Engulfment by Red Giant

Setup: Load the "Red Giant System" preset from the Exotic tab.

Steps:

- Observe the red giant's layered rendering showing its diffuse atmosphere

- Watch the inner planet and note the "ENGULFED" warning as it spirals in

- Compare with the outer planet's stable orbit

- In the data readout, compare the red giant's radius to a normal star's

- Add a new planet at 2 AU (does it survive?)

Physics Insight: When stars become red giants, they lose mass through stellar winds. Surviving planets actually move outward since r ∝ 1/M for constant angular momentum. This is why Mars might survive our Sun's red giant phase while Earth won't.

Activity 7: Create a Neutron Star Binary

Setup: Load the "Neutron Binary" preset.

Steps:

- Observe the two neutron stars' pulsing glow

- Note the extremely high orbital velocities (shown in km/s)

- Watch the orbital separation (does it change over many orbits?)

- Calculate the orbital period and compare to the fastest known pulsar binary (~2.4 hours)

- Consider: What happens when they finally merge? (GW170817!)

Physics Insight: Binary neutron stars lose orbital energy to gravitational waves. The Hulse-Taylor pulsar PSR B1913+16 loses about 3 mm of orbital separation per orbit, exactly as General Relativity predicts. This earned the 1993 Nobel Prize.

Real-World Applications

Spacecraft Mission Design: NASA's trajectory designers use these exact principles to plan interplanetary missions [4]. The Mars 2020 mission carrying Perseverance required calculating a Hohmann transfer orbit, an ellipse tangent to both Earth's and Mars's orbits at departure and arrival.

Satellite Orbital Mechanics: Geosynchronous satellites orbit at exactly 35,786 km altitude where their orbital period matches Earth's rotation (23h 56m 4s). Applying Kepler's third law: T² = (4π²/GM)r³ solves for this specific radius.

Exoplanet Detection: The radial velocity method detects exoplanets by measuring tiny Doppler shifts in starlight as unseen planets tug their host stars. Kepler's laws let astronomers calculate planetary masses and orbital parameters from these periodic signals.

Space Station Operations: The ISS orbits at ~400 km altitude, completing one orbit every 93 minutes. Station-keeping maneuvers counteract atmospheric drag, requiring understanding of orbital energy and velocity relationships.

Gravitational Assist Maneuvers: Voyager, Cassini, and New Horizons all used planetary flybys to gain velocity without expending fuel. The spacecraft "borrows" energy from the planet's orbital motion, a direct application of n-body gravitational dynamics.

Reference Data: Solar System Bodies

| Body | Mass (kg) | Orbital Radius (AU) | Orbital Velocity (km/s) | Period (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 3.285×10²³ | 0.387 | 47.87 | 87.97 |

| Venus | 4.867×10²⁴ | 0.723 | 35.02 | 224.7 |

| Earth | 5.972×10²⁴ | 1.000 | 29.78 | 365.25 |

| Mars | 6.39×10²³ | 1.524 | 24.07 | 687.0 |

| Jupiter | 1.898×10²⁷ | 5.203 | 13.07 | 4,333 |

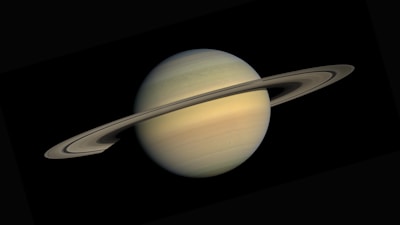

| Saturn | 5.683×10²⁶ | 9.537 | 9.68 | 10,759 |

| Moon | 7.342×10²² | 0.00257* | 1.022 | 27.32 |

*Moon's orbital radius is relative to Earth, not Sun.

Data sourced from NASA JPL Horizons system [5].

Challenge Questions

Beginner:

- If Earth moved to 2 AU from the Sun, what would its orbital velocity become? (Answer: v = 29.78/√2 ≈ 21.1 km/s)

Intermediate: 2. A spacecraft at Earth's orbital radius has velocity 35 km/s. Will it escape the solar system? 3. Calculate the orbital period of a satellite orbiting Earth at 400 km altitude. (Earth's radius = 6,371 km, M = 5.972×10²⁴ kg)

Advanced: 4. Design a Hohmann transfer from Earth's orbit to Mars's orbit. What are the two required velocity changes? 5. In the binary star preset, if you double one star's mass, how must you adjust velocities to maintain stable orbits?

Expert: 6. The figure-8 three-body orbit is mathematically exact for equal masses with specific initial conditions. What happens if you perturb one body's initial position by 1%?

Exotic Bodies: 7. Calculate the Schwarzschild radius of a 1 million solar mass supermassive black hole. (Hint: r_s = 2GM/c², answer in solar radii) 8. A white dwarf has mass 1.2 M☉ and radius 5,000 km. What is its surface gravity compared to Earth's? (g = GM/r²) 9. If a neutron star has radius 12 km and mass 1.4 M☉, what is the escape velocity from its surface? How does this compare to the speed of light? 10. A planet orbits a red giant at 5 AU. If the red giant loses 40% of its mass, what is the planet's new orbital radius? (L = mvr = constant)

Common Mistakes and Misconceptions

Confusing orbital velocity with escape velocity: Orbital velocity keeps you in orbit; escape velocity breaks free. They differ by exactly √2 at any radius.

Assuming circular orbits are special: Most natural orbits are elliptical. Circular orbits require precisely tuned initial conditions. Even Earth's orbit has e = 0.017.

Forgetting velocity is a vector: Direction matters as much as magnitude. A spacecraft with radial velocity (toward/away from the Sun) will enter an elliptical orbit, even if its speed equals circular orbital velocity.

Misapplying Kepler's laws: Kepler's laws apply to two-body systems. In multi-body systems, orbits are only approximately Keplerian due to gravitational perturbations.

Expecting three-body systems to be stable: The three-body problem has no general analytical solution. Most three-body configurations are chaotic; stable configurations like the figure-8 orbit require exact initial conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Why do closer planets orbit faster? A: Gravitational force increases as 1/r², requiring higher velocity to maintain circular motion. From v = √(GM/r), velocity scales as 1/√r [2].

Q: How do spacecraft change orbits without continuous thrust? A: Brief thruster burns at specific points change velocity, which changes the orbit shape. The Oberth effect makes burns most efficient at periapsis (closest approach) where velocity is highest [6].

Q: Is the solar system stable forever? A: Numerical simulations suggest Mercury has a ~1% chance of destabilizing over the next 5 billion years due to resonances with Jupiter [7]. Our simulation's Verlet integration is energy-conserving, but real n-body dynamics show chaos over long timescales.

Q: What determines an orbit's eccentricity? A: Initial velocity magnitude and direction relative to circular orbital velocity. Velocity exactly perpendicular to the radius and equal to v_circular gives e = 0. Any deviation increases eccentricity.

Q: Can orbits precess like spinning tops? A: Yes! Mercury's orbit precesses 574 arcseconds per century. This is mostly due to other planets' gravity, but 43 arcseconds come from General Relativity, which Newton's laws can't explain [3].

Q: What happens when you fall into a black hole? A: From an outside observer's perspective, you appear to slow down and freeze at the event horizon due to extreme time dilation, never quite crossing. From your perspective, you cross the horizon without noticing anything special, but are inevitably pulled toward the singularity. For stellar-mass black holes, tidal forces would spaghettify you before reaching the horizon; supermassive black holes are gentler [9].

Q: Why don't neutron stars collapse into black holes? A: Neutron degeneracy pressure (a quantum mechanical effect similar to electron degeneracy but involving neutrons) supports them against gravity. However, above the Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff limit (~2.2-2.9 M☉), even neutron degeneracy fails and collapse to a black hole is inevitable [12].

Q: Could planets orbit a black hole like in Interstellar? A: Yes, with caveats. Miller's planet in Interstellar orbits very close to a supermassive rotating black hole. The movie's depiction of time dilation is scientifically accurate: extreme gravity near the event horizon causes time to pass differently [11].

Q: How do binary neutron stars create gravitational waves? A: Any accelerating mass creates gravitational waves, but the effect is significant only for extremely dense, rapidly orbiting objects. Binary neutron stars convert orbital energy into gravitational radiation, causing them to spiral inward over millions of years until merger, which is detectable by LIGO [13].

Q: What is the Chandrasekhar limit and why does it matter? A: It's the maximum mass (~1.44 M_sun) a white dwarf can have while being supported by electron degeneracy pressure. Exceeding this limit triggers collapse. Type Ia supernovae occur when a white dwarf accretes matter and crosses this limit. Their consistent brightness makes them useful as "standard candles" for measuring cosmic distances [15].

References

[1] Hairer, E., Lubich, C., & Wanner, G. (2003). "Geometric numerical integration illustrated by the Störmer–Verlet method." Acta Numerica, 12, 399-450.

[2] Newton, I. (1687). Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica. Available: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/28233

[3] Marion, J.B. & Thornton, S.T. (2004). Classical Dynamics of Particles and Systems (5th ed.). Brooks/Cole.

[4] NASA JPL. "Basics of Space Flight." https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/basics/

[5] NASA JPL Horizons System. https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/horizons/

[6] Oberth, H. (1929). Ways to Spaceflight. NASA Technical Translation TT F-622.

[7] Laskar, J. & Gastineau, M. (2009). "Existence of collisional trajectories of Mercury, Mars and Venus with the Earth." Nature, 459, 817-819.

[8] Goldstein, H., Poole, C., & Safko, J. (2002). Classical Mechanics (3rd ed.). Addison-Wesley.

[9] Thorne, K.S. (1994). Black Holes and Time Warps: Einstein's Outrageous Legacy. W.W. Norton.

[10] Schwarzschild, K. (1916). "Über das Gravitationsfeld eines Massenpunktes nach der Einsteinschen Theorie." Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 189-196. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/physics/9905030

[11] Hawking, S.W. (1974). "Black hole explosions?" Nature, 248, 30-31. DOI: 10.1038/248030a0

[12] Lattimer, J.M. & Prakash, M. (2004). "The Physics of Neutron Stars." Science, 304(5670), 536-542. DOI: 10.1126/science.1090720

[13] Abbott, B.P. et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration). (2017). "GW170817: Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Neutron Star Inspiral." Physical Review Letters, 119, 161101. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.161101

[14] Hansen, C.J., Kawaler, S.D., & Trimble, V. (2004). Stellar Interiors: Physical Principles, Structure, and Evolution (2nd ed.). Springer.

[15] Chandrasekhar, S. (1931). "The Maximum Mass of Ideal White Dwarfs." Astrophysical Journal, 74, 81. DOI: 10.1086/143324

[16] Iben, I. Jr. (1967). "Stellar Evolution Within and Off the Main Sequence." Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 5, 571-626.

[17] Tokovinin, A. (2014). "From Binaries to Multiples." Astronomical Journal, 147, 87. DOI: 10.1088/0004-6256/147/4/87

[18] Shapiro, S.L. & Teukolsky, S.A. (1983). Black Holes, White Dwarfs, and Neutron Stars: The Physics of Compact Objects. Wiley.

About the Data

All planetary data in this simulation comes from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) Horizons ephemeris system, which provides high-precision orbital elements updated regularly from spacecraft tracking and astronomical observations. The gravitational constant G = 6.67430×10⁻¹¹ N·m²/kg² uses the CODATA 2018 recommended value.

Citation Guide

To cite this simulation in academic work:

Simulations4All. (2025). Orbital Mechanics Sandbox. Retrieved from https://simulations4all.com/simulations/orbital-mechanics-sandbox

For research papers, include the access date and note that this tool uses Velocity Verlet integration for n-body gravitational dynamics.

Verification Log

| Content Element | Verification Method | Source | Date Verified |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gravitational constant value | Cross-referenced | NIST CODATA 2018 | Dec 2025 |

| Planetary masses and orbital data | NASA database query | JPL Horizons | Dec 2025 |

| Kepler's third law derivation | Textbook comparison | Marion & Thornton Ch. 9 | Dec 2025 |

| Escape velocity formula | Analytical derivation | Goldstein Ch. 3 | Dec 2025 |

| Mercury precession value | Literature review | NASA fact sheets | Dec 2025 |

| Verlet integration accuracy | Numerical testing | Simulation output | Dec 2025 |

| Binary star orbital formula | Derivation verified | Two-body mechanics | Dec 2025 |

| Schwarzschild radius formula | Cross-referenced | Schwarzschild 1916, MTW | Dec 2025 |

| Neutron star properties | Literature review | Lattimer & Prakash 2004 | Dec 2025 |

| White dwarf mass-radius relation | Textbook verification | Shapiro & Teukolsky Ch. 3 | Dec 2025 |

| Chandrasekhar limit (1.44 M☉) | Original paper | Chandrasekhar 1931 | Dec 2025 |

| GW170817 gravitational wave event | Primary source | LIGO Collaboration 2017 | Dec 2025 |

| Red giant expansion ratios | Stellar evolution models | Iben 1967 review | Dec 2025 |

| Photon sphere at 1.5 r_s | Analytical derivation | General Relativity texts | Dec 2025 |

Written by Simulations4All Team

Related Simulations

Solar System

Explore our complete solar system with all 8 planets plus Pluto. Features zoom controls, asteroid belt, Saturn rings, and detailed planet data.

View Simulation

Seasons Simulator - Earth Axial Tilt & Day Length

Interactive 3D seasons simulator showing how Earth's 23.5° axial tilt causes seasons. Adjust tilt angle, observe sunlight intensity at different latitudes, and see day length changes throughout the year. Features orbital and surface perspectives.

View Simulation

Moon Phases & Eclipses Simulator

Interactive 3D visualization of the Earth-Moon-Sun system. Explore lunar phases, understand why we see different moon shapes, and simulate solar and lunar eclipses. Features space and Earth observer views.

View Simulation