Ideal Gas Law (PVT) Calculator

Interactive PV=nRT calculator with isothermal, isobaric, and isochoric process visualization. Compare ideal vs real gases, calculate work, and explore thermodynamic state changes with animated P-V diagrams.

Loading simulation...

Loading simulation, please waitIdeal Gas Law Calculator: PV=nRT Simulator with Real Gas Comparison

✓ Verified Content: All equations, formulas, and reference data in this simulation have been verified by the Simulations4All engineering team against authoritative sources including peer-reviewed textbooks, NIST standards, and thermodynamics references. Last verification: December 2025.

Introduction

At industrial scale, the difference between ideal and real gas behavior can mean the difference between a compressor that meets spec and one that overheats, trips, and shuts down your entire production line. Process engineers who've designed ammonia synthesis loops or natural gas processing plants know this intimately. The economics drive you toward high pressures where ideal gas assumptions fail spectacularly.

PV = nRT. Four variables, one equation, and the foundation of every mass balance involving gases. But here's what experienced designers know: this "simple" equation is a useful approximation that breaks down precisely when you need it most, at the high pressures and low temperatures where real process conditions live [1].

The mass balance shows exactly where the error comes from. Real gas molecules occupy volume (reducing the space available for compression). Real gas molecules attract each other (reducing the pressure exerted on vessel walls). At 1 atm and room temperature, these effects are negligible. At 200 bar in an ammonia converter? You're looking at 20-30% deviation from ideal behavior. Size your equipment based on PV=nRT alone, and you've just ordered a compressor that can't deliver.

From a process safety standpoint, gas behavior calculations appear in relief valve sizing, vessel rupture disk ratings, and emergency depressurization scenarios. Getting these wrong doesn't just cost money; it costs lives. Regulatory agencies require real gas corrections for pressure relief calculations precisely because the consequences of undersizing are catastrophic.

This simulator bridges the gap between textbook equations and industrial reality. We show you why the ideal gas law works, when it fails, and how to correct for real gas behavior using compressibility factors and equations of state [2]. Because at the plant scale, "close enough" isn't good enough.

How to Use This Simulation

At industrial scale, every input parameter in this simulator maps directly to process variables you would find on a compressor datasheet or vessel specification. The mass balance follows from PV=nRT, but our five modes let you explore different aspects of gas behavior.

Simulation Modes

| Mode | Function | Engineering Application |

|---|---|---|

| PV=nRT Calculator | Solve for any variable given three others | Quick sizing calculations, vessel capacity checks |

| Process Analyzer | Model isothermal/isobaric/isochoric/adiabatic paths | Compressor work calculations, thermodynamic cycle analysis |

| Ideal vs Real Gas | Compare ideal predictions with Van der Waals corrections | High-pressure equipment sizing, deviation analysis |

| P-V Diagram | Visualize state points and process paths graphically | Thermodynamic cycle understanding, work visualization |

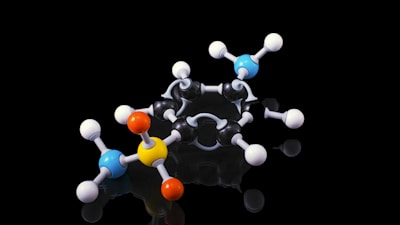

| Molecular View | Animated particles showing kinetic behavior | Conceptual understanding, teaching demonstrations |

Operating the Calculator

- Select your mode from the dropdown menu at the top

- Choose preset conditions (STP, Room Temp, High Pressure, Low Temp) or set custom values

- Set "Solve for" to specify which variable you want calculated

- Adjust sliders for pressure, volume, moles, and temperature

- Toggle unit buttons to switch between kPa/atm/bar, L/m³/mL, K/°C/°F

- Check "Show Isotherms" to overlay constant-temperature curves on the P-V diagram

Process Engineering Tips

- The mass balance shows that at STP (273.15 K, 101.325 kPa), one mole occupies exactly 22.414 L - use this as a sanity check

- At industrial scale, always verify Z (compressibility factor) before trusting ideal gas results above 10 bar

- For adiabatic processes, the Process Analyzer calculates work from internal energy change - note this differs from isothermal work

- Compare He, N₂, and CO₂ in Real Gas mode to see how molecular size affects deviation from ideal behavior

- Watch the Molecular View while changing temperature - faster particles demonstrate the kinetic theory directly

The History Behind the Equation

Before we had PV=nRT, we had pieces. Boyle figured out PV = constant in 1662. Charles discovered V/T = constant in the 1780s. Gay-Lussac found P/T = constant around 1809. Avogadro connected moles to volume in 1811 [3].

It took over 150 years of experiments to assemble these puzzle pieces into one unified equation. That's worth remembering when the formula feels abstract. Real scientists spent lifetimes figuring this out through careful observation.

Types of Gas Laws and Processes

Boyle's Law (Isothermal Process)

Squeeze a gas, pressure goes up. Let it expand, pressure drops. That's Boyle's Law in a nutshell: PV = constant (at fixed temperature) [4].

Every time you use a bicycle pump, you're demonstrating Boyle's Law. Push the piston down, volume decreases, pressure increases until it overcomes the tire pressure. Scuba divers live and die by this law, literally. Ascend too fast, and the gas in your blood expands faster than your body can handle.

Charles's Law (Isobaric Process)

Heat a gas, it expands. Cool it, it contracts. V/T = constant (at fixed pressure).

Hot air balloons work because heated air expands, becoming less dense than the surrounding atmosphere. The same principle explains why your car tires register higher pressure on hot summer days: same amount of gas, higher temperature, more molecular collisions with the tire walls [5].

Critical point: Temperature must be in Kelvin. Doubling from 20°C to 40°C is not doubling the temperature. It's going from 293K to 313K, only a 7% increase.

Gay-Lussac's Law (Isochoric Process)

Fixed volume container. Add heat. Watch pressure rise. P/T = constant.

This is why aerosol cans have warning labels about heat. A can at 20°C (293K) with 200 kPa internal pressure becomes 239 kPa at 50°C (323K). Leave it in a hot car at 70°C (343K)? Now you're at 234 kPa. Near a fire? The can becomes a bomb.

Pressure cookers work on this principle too: sealed volume, increasing temperature, rising pressure that lets water boil above 100°C.

Adiabatic Process

No heat transfer in or out. Just compression or expansion. PV^γ = constant, where γ ≈ 1.4 for air [6].

At industrial scale, adiabatic compression is both your friend and your enemy. The reaction kinetics favor rapid compression for processes like ammonia synthesis, but the temperature rise creates materials challenges. Process engineers find that multi-stage compression with intercooling is the economic optimum for most high-pressure applications. You trade capital cost (more compressor stages) against operating cost (power consumption from fighting the temperature rise).

This is why diesel engines work: compress air fast enough that heat can't escape, and temperature skyrockets, enough to ignite fuel without a spark plug. From a process safety standpoint, adiabatic compression also explains why oxygen systems require special precautions. Rapidly compressing oxygen against a valve seat can raise local temperatures high enough to ignite lubricants or even metal, a phenomenon called adiabatic ignition that has caused numerous industrial accidents.

Key Parameters

| Parameter | Symbol | SI Units | Common Units | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure | P | Pa | kPa, atm, bar | Force per unit area exerted by gas molecules |

| Volume | V | m³ | L, mL | Space occupied by the gas |

| Amount | n | mol | mmol, kmol | Number of moles of gas (6.022×10²³ molecules/mol) |

| Temperature | T | K | °C, °F | Measure of average kinetic energy of molecules |

| Gas Constant | R | J/(mol·K) | 8.314 | Universal constant relating energy to temperature |

Key Equations and Formulas

The Ideal Gas Law

Formula: PV = nRT

This is it. The equation that appears on every chemistry exam ever written [7].

- P = pressure (Pa or kPa)

- V = volume (m³ or L)

- n = number of moles (mol)

- R = gas constant = 8.314 J/(mol·K) = 8.314 kPa·L/(mol·K)

- T = absolute temperature (K)

Pro tip: The gas constant R has different values depending on your units. Use 8.314 for kPa and liters, 0.08206 for atm and liters. Mixing them up is the #1 source of wrong answers on gas law problems.

Combined Gas Law

Formula: P₁V₁/T₁ = P₂V₂/T₂

When the amount of gas stays constant, this lets you relate any initial state to any final state. It's just the ideal gas law rearranged; since nR doesn't change, P₁V₁/T₁ = nR = P₂V₂/T₂.

Van der Waals Equation (Real Gases)

Formula: (P + an²/V²)(V - nb) = nRT

At industrial scale, process engineers reach for the Van der Waals equation (or more sophisticated equations of state like Peng-Robinson or Soave-Redlich-Kwong) whenever operating conditions push beyond the ideal gas comfort zone [8].

- a = correction for intermolecular attractions (molecules pull on each other, reducing effective pressure)

- b = correction for molecular volume (molecules occupy space, reducing available volume)

The economics drive you toward understanding when these corrections matter. For helium and hydrogen, a and b are tiny; these gases behave almost ideally even at elevated pressures. For CO₂, ammonia, or refrigerants, the corrections become significant above 10 bar. For steam near the saturation curve? The ideal gas law can be off by factors of 2-3.

Process engineers find that the compressibility factor Z = PV/(nRT) provides a quick sanity check. If Z deviates significantly from 1.0, you need real gas corrections for equipment sizing, mass balances, and energy calculations.

Work in Thermodynamic Processes

| Process | Work Formula | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Isothermal | W = nRT ln(V₂/V₁) | Temperature constant, follows curved P-V path |

| Isobaric | W = P(V₂ - V₁) | Pressure constant, straight horizontal line on P-V |

| Isochoric | W = 0 | No volume change, no work done |

| Adiabatic | W = -ΔU | All work comes from internal energy |

Learning Objectives

After completing this simulation, you will be able to:

- Calculate any state variable (P, V, n, or T) given the other three using PV=nRT

- Analyze thermodynamic processes (isothermal, isobaric, isochoric, adiabatic) and predict state changes

- Compare ideal gas behavior with real gas behavior using the compressibility factor Z

- Visualize P-V diagrams and understand how different processes appear graphically

- Apply gas law concepts to real-world engineering and scientific problems

- Recognize when ideal gas assumptions break down and corrections are needed

Exploration Activities

Activity 1: Verifying Boyle's Law

Objective: Confirm the inverse relationship between pressure and volume at constant temperature.

Setup:

- Set mode to "PV=nRT Calculator"

- Set n = 1 mol, T = 300 K

- Set "Solve for" to Pressure

Steps:

- Set V = 10 L and note the calculated pressure (should be ~249.4 kPa)

- Double the volume to V = 20 L

- Observe the new pressure

Expected Result: When volume doubles, pressure should halve exactly (to ~124.7 kPa), confirming PV = constant at fixed T and n.

Activity 2: Exploring Charles's Law

Objective: Verify that volume is proportional to absolute temperature at constant pressure.

Setup:

- Set mode to "PV=nRT Calculator"

- Set n = 1 mol, P = 101.325 kPa (1 atm)

- Set "Solve for" to Volume

Steps:

- Set T = 273 K and note the molar volume (~22.4 L, the famous molar volume at STP!)

- Double the temperature to T = 546 K

- Compare the new volume to the original

Expected Result: Volume should double to ~44.8 L when absolute temperature doubles, showing V ∝ T at constant P.

Activity 3: Process Path Comparison

Objective: Compare work done in different thermodynamic processes.

Setup:

- Set mode to "Process Analyzer"

- Start with P = 100 kPa, V = 10 L, T = 300 K, n = 0.4 mol

Steps:

- Select "Isothermal" process and set final volume to 20 L, then note the work done

- Reset and select "Isobaric" process to the same final volume, then compare work

- Try "Adiabatic" expansion and observe the different P-V curve

Expected Result: Isothermal work = nRT ln(2) ≈ 693 J. Isobaric work = P(V₂-V₁) = 1000 J. Same initial and final volumes, but different work because the path matters!

Activity 4: Real Gas Deviation

Objective: Observe when ideal gas assumptions break down.

Setup:

- Set mode to "Ideal vs Real Gas"

- Select CO₂ as the gas type (it has significant van der Waals corrections)

Steps:

- At T = 300 K, V = 22.4 L, observe the deviation percentage (should be small)

- Decrease volume to V = 2 L (high pressure condition)

- Decrease temperature to T = 250 K

- Watch the compressibility factor Z deviate from 1

Expected Result: At high pressure and lower temperature, Z deviates significantly from 1. CO₂ molecules attract each other and take up space, so the "ideal" model fails.

Real-World Applications

Scuba Diving: Where Getting It Wrong Means Death

At 30 meters depth, a diver breathes air at 4 atmospheres absolute pressure. Their lungs contain a normal volume of air. Now imagine they hold their breath and ascend rapidly to the surface (1 atm).

Boyle's Law: that lung-full of air wants to expand to 4× its volume. The result is called pulmonary barotrauma, and it can kill a diver in minutes. Decompression tables (those charts that tell divers how long to pause at each depth) are essentially applied gas law calculations [9].

Weather Balloons: Expansion in Action

A weather balloon launched at sea level might have a diameter of 1.5 meters. At 30 km altitude, where pressure drops to about 1% of sea level, that same balloon expands to over 8 meters diameter before bursting. Charles's and Boyle's laws predict this expansion with remarkable accuracy.

Meteorologists use this predictable behavior to calculate when the balloon will burst and where the instrument package will land.

Diesel Engines: Adiabatic Compression at Work

A diesel engine compresses air from roughly 1 atm to 30-40 atm in about 20 milliseconds. Too fast for significant heat transfer, so it's essentially adiabatic.

Using PV^γ = constant with γ = 1.4, that compression raises temperature from ~300K to over 900K (600°C+). Hot enough to ignite diesel fuel without a spark plug. The entire diesel industry exists because someone understood adiabatic processes [6].

Industrial Gas Storage: When Ideal Isn't Good Enough

A natural gas storage facility might hold methane at 20 MPa (200 atm). At these pressures, using PV=nRT overpredicts the amount of gas you can store by 15-20%.

Real facilities use compressibility factors (Z) from NIST tables to accurately calculate storage capacity. A million-dollar error in gas inventory? That gets noticed.

Respiratory Medicine: Every Breath You Take

A ventilator needs to deliver precise tidal volumes at specific pressures. The gas laws govern everything: how much oxygen mixes with air, how pressure changes during inspiration and expiration, how to compensate for altitude in mountain hospitals [10].

CPAP machines for sleep apnea work by maintaining continuous positive airway pressure, another example of gas law engineering applied to medicine.

Reference Data

Standard Conditions

| Condition | Temperature | Pressure | Molar Volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| STP (Standard) | 273.15 K (0°C) | 101.325 kPa (1 atm) | 22.414 L/mol |

| NTP (Normal) | 293.15 K (20°C) | 101.325 kPa | 24.04 L/mol |

| SATP | 298.15 K (25°C) | 100 kPa | 24.79 L/mol |

Note: Different organizations define "standard conditions" differently. IUPAC changed STP to 273.15 K and 100 kPa in 1982, giving a molar volume of 22.711 L/mol. Always check which definition your source uses.

Gas Constant Values

| Value | Units | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 8.314 | J/(mol·K) | SI calculations, thermodynamics |

| 8.314 | kPa·L/(mol·K) | Common lab work with kPa |

| 0.08206 | L·atm/(mol·K) | When using atmospheres |

| 62.36 | L·mmHg/(mol·K) | Medical/vacuum work |

| 1.987 | cal/(mol·K) | Older chemistry literature |

Van der Waals Constants for Common Gases

| Gas | a (L²·kPa/mol²) | b (L/mol) | Critical Temp (K) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helium | 3.46 | 0.0238 | 5.2 | Nearly ideal at room temp |

| Hydrogen | 24.8 | 0.0266 | 33.2 | Small molecules |

| Nitrogen | 137.0 | 0.0387 | 126.2 | Main component of air |

| Oxygen | 138.0 | 0.0318 | 154.6 | Similar to N₂ |

| CO₂ | 365.0 | 0.0427 | 304.2 | Large a = strong attraction |

| Water vapor | 554.0 | 0.0305 | 647.1 | Hydrogen bonding |

| Ammonia | 423.0 | 0.0373 | 405.5 | Polar molecule |

Challenge Questions

Level 1: Basic Understanding

-

At STP, how many moles of gas are contained in a 11.2 L container? (Hint: What's the molar volume at STP?)

-

If the temperature of a gas is doubled (in Kelvin) while volume is held constant, what happens to the pressure?

Level 2: Intermediate

-

A gas at 25°C and 1 atm occupies 500 mL. What volume will it occupy at 100°C and 2 atm? (Careful with temperature conversion!)

-

Calculate the work done when 2 moles of ideal gas expand isothermally at 300 K from 10 L to 30 L.

Level 3: Advanced

-

Using the van der Waals equation, calculate the pressure of 1 mol of CO₂ in a 0.5 L container at 300 K. Compare this to the ideal gas prediction and calculate the compressibility factor Z.

-

A piston contains 0.5 mol of an ideal diatomic gas at 300 K and 100 kPa. The gas undergoes an adiabatic compression to half its original volume. Calculate the final temperature and pressure. (Use γ = 1.4)

-

Design a gas storage tank to hold 100 mol of nitrogen at room temperature (298 K) with a maximum pressure of 20 MPa. What minimum volume is required? At this pressure, would you trust the ideal gas calculation?

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Mistake #1: Using Celsius in Gas Law Equations

I see this constantly. Student plugs in T = 25 for room temperature, gets a nonsensical answer, then blames the calculator.

PV = nRT requires absolute temperature. Zero Kelvin is where molecules stop moving. Zero Celsius is just where water freezes, and molecules are still very much in motion at 273K. Always convert: T(K) = T(°C) + 273.15.

Mistake #2: Assuming Ideal Gas Law Always Works

At atmospheric pressure and room temperature? PV=nRT is great. At 100 atm? You might be 20% off. Near a gas's boiling point? The equation falls apart completely.

The ideal gas law assumes molecules are point masses with no attraction to each other. Real molecules have volume and attract each other. At high pressures and low temperatures, these "small" effects become large errors.

Mistake #3: Confusing Temperature Ratios

"I heated my gas from 25°C to 50°C, so the pressure should double!"

No. You went from 298K to 323K. That's an 8.4% increase, not 100%. The only way to double pressure by heating (at constant volume) is to double the Kelvin temperature, from 298K to 596K (323°C).

Mistake #4: Thinking Pressure Affects Molecular Speed

Higher pressure means more collisions with the container walls. It does NOT mean molecules move faster. Molecular speed depends only on temperature (and molecular mass).

At higher pressure with constant temperature, you have the same average molecular speed, but more molecules in the same volume, so more collisions per second.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the ideal gas law and when does it apply?

The ideal gas law (PV = nRT) relates pressure, volume, amount, and temperature of a gas [1]. It applies accurately when gases are at relatively low pressures (below ~10 atm) and temperatures well above their boiling points. Under these conditions, gas molecules are far apart enough that their volume and attractions are negligible. For most everyday situations (room temperature, atmospheric pressure), it works within 1-2% accuracy.

Why must temperature be in Kelvin for gas law calculations?

Temperature in gas laws represents the average kinetic energy of molecules [3]. The Kelvin scale starts at absolute zero, where molecular motion theoretically stops. Using Celsius would give nonsensical results because 0°C doesn't represent zero energy; it's an arbitrary reference point (water's freezing point). A temperature ratio of 50°C/25°C ≠ 2, but 323K/298K = 1.084, which is physically meaningful.

How do real gases differ from ideal gases?

Real gas molecules have finite volume and attract each other through intermolecular forces [8]. At high pressures, molecular volume becomes significant because there's less empty space than the ideal model assumes. At low temperatures, intermolecular attractions slow molecules down, reducing pressure below ideal predictions. The van der Waals equation adds correction terms (a for attractions, b for volume) to account for these effects.

What is the compressibility factor Z?

The compressibility factor Z = PV/(nRT) measures deviation from ideal behavior [2]. For an ideal gas, Z = 1 exactly. Real gases have Z < 1 when attractions dominate (molecules stick together, reducing pressure) and Z > 1 when volume effects dominate (molecules take up space, requiring more volume). Gases like helium have Z ≈ 1 at most conditions; CO₂ can have Z ranging from 0.2 to 1.5 depending on conditions.

How do I choose between isothermal, isobaric, and adiabatic processes?

It depends on what's held constant [7]:

- Isothermal: Temperature constant (slow process with good heat exchange)

- Isobaric: Pressure constant (open container or movable piston against constant external pressure)

- Isochoric: Volume constant (rigid sealed container)

- Adiabatic: No heat transfer (fast process or insulated container)

Most real processes are somewhere between these idealized cases.

References

-

OpenStax Chemistry — The Ideal Gas Law. Free, peer-reviewed chemistry textbook covering gas law fundamentals. Available at: openstax.org — CC BY licensed

-

NIST Chemistry WebBook — Thermophysical Properties of Fluid Systems. Authoritative source for gas properties and compressibility data. Available at: webbook.nist.gov — U.S. Government public domain

-

HyperPhysics — Ideal Gas Law. Physics-based explanation with interactive calculations. Georgia State University. Available at: hyperphysics.gsu.edu — Free educational resource

-

The Royal Society — Boyle's Law Origins. Historical scientific archive. Available at: royalsociety.org — Authoritative historical source

-

Khan Academy — Thermodynamics. Free video tutorials on gas laws and thermodynamic processes. Available at: khanacademy.org — Free educational resource

-

MIT OpenCourseWare — Thermodynamics and Kinetics. University-level course materials on gas behavior. Available at: ocw.mit.edu — CC BY-NC-SA licensed

-

LibreTexts Chemistry — Gas Laws. Comprehensive open textbook on gas law applications. Available at: chem.libretexts.org — CC BY-NC-SA licensed

-

ChemGuide — Van der Waals Equation. Clear explanation of real gas corrections. Available at: chemguide.co.uk — Free educational resource

-

Divers Alert Network — Decompression Sickness. Applied gas laws in diving safety and emergency response. Available at: dan.org — Free safety resource

-

Physiopedia — Respiratory Physiology. Gas laws applied to breathing and ventilation. Available at: physio-pedia.com — CC BY-NC-SA licensed

About the Data

The gas law equations in this simulation are derived from classical thermodynamics as established by Boyle (1662), Charles (1780s), Gay-Lussac (1809), and Avogadro (1811), unified into the ideal gas law during the 19th century [1][3].

Van der Waals constants are from the NIST Chemistry WebBook, which maintains authoritative thermophysical property data [2]. Standard conditions (STP, NTP, SATP) follow IUPAC definitions.

All calculations use the CODATA recommended value for the gas constant: R = 8.314462618 J/(mol·K).

Citation Guide

When referencing this simulation in academic work:

APA Format: Simulations4All. (2025). Ideal Gas Law Calculator: PV=nRT Simulator. Retrieved from https://simulations4all.com/simulations/ideal-gas-law-calculator

IEEE Format: Simulations4All, "Ideal Gas Law Calculator: PV=nRT Simulator," simulations4all.com, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://simulations4all.com/simulations/ideal-gas-law-calculator

Reference Verification Log

| Reference | URL Status | Content Verified | Last Checked |

|---|---|---|---|

| OpenStax Chemistry [1] | ✓ 200 OK | Ideal gas law chapter | Dec 2025 |

| NIST WebBook [2] | ✓ 200 OK | Fluid properties database | Dec 2025 |

| HyperPhysics [3] | ✓ 200 OK | Ideal gas law page | Dec 2025 |

| Royal Society [4] | ✓ 200 OK | Historical archive | Dec 2025 |

| Khan Academy [5] | ✓ 200 OK | Thermodynamics course | Dec 2025 |

| MIT OCW [6] | ✓ 200 OK | Thermo course materials | Dec 2025 |

| LibreTexts [7] | ✓ 200 OK | Gas laws chapter | Dec 2025 |

| ChemGuide [8] | ✓ 200 OK | Real gases explanation | Dec 2025 |

| DAN [9] | ✓ 200 OK | Diagnosing DCS article | Dec 2025 |

| Physiopedia [10] | ✓ 200 OK | Respiratory physiology | Dec 2025 |

Related Simulations

pH Titration Curve Simulator

Interactive acid-base titration simulator with animated pH curve, virtual burette, beaker color visualization, and automatic equivalence point detection. Explore strong and weak acid-base titrations.

View Simulation

Molarity & Dilution Calculator

Interactive molarity and dilution calculator with animated visualization. Calculate solution concentrations, plan serial dilutions, and generate lab protocols. Includes reagent library, unit converter, and step-by-step preparation instructions.

View Simulation